By Kyle Hur and Nora Lowe

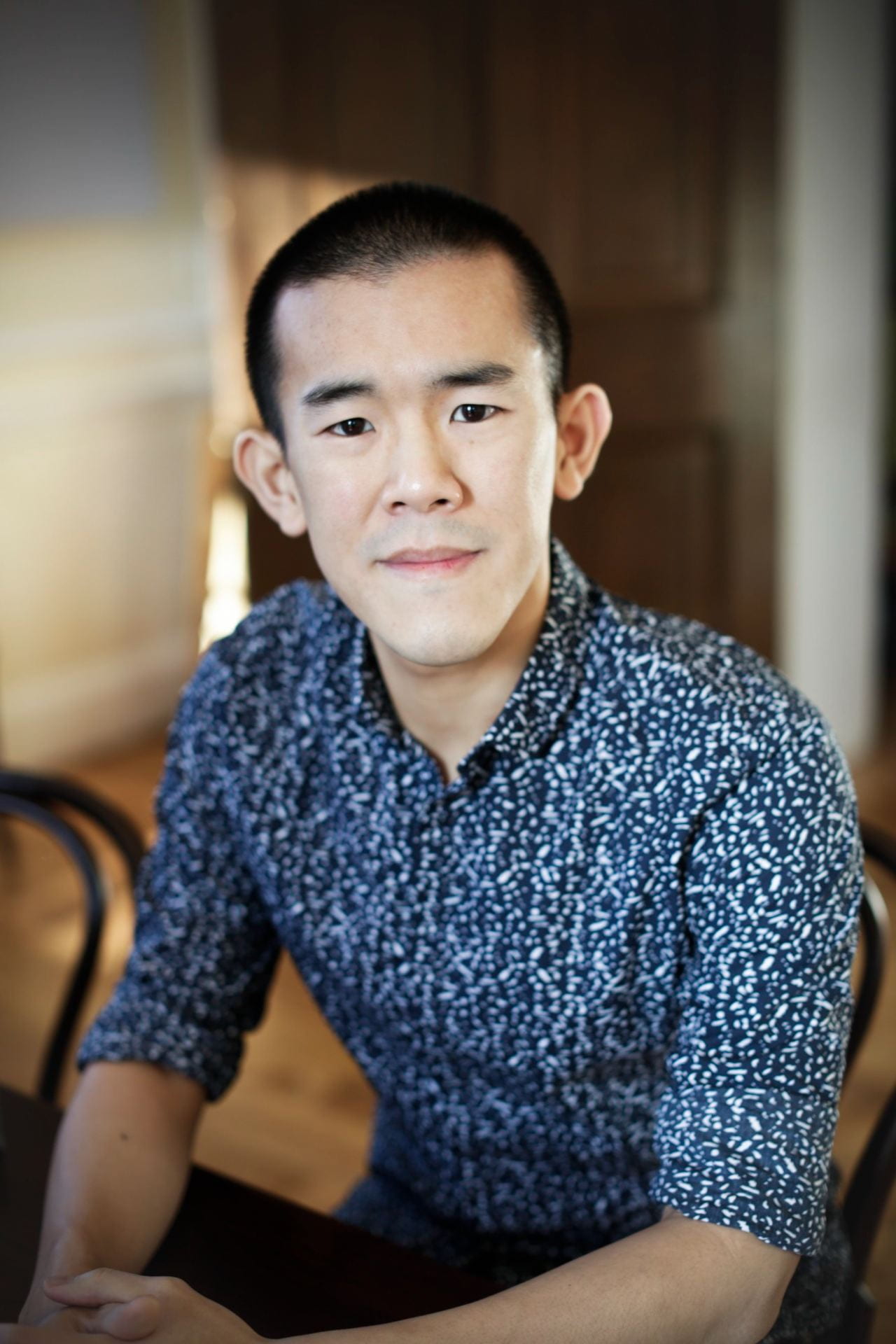

Ed Yong is a science journalist and the author of two New York Times bestsellers. He has received national recognition for his science writing, including winning the Pulitzer Prize in explanatory journalism and the Victor Cohn Prize for medical science reporting. The Amherst STEM Network had the pleasure of interviewing Yong about his journey in science journalism, as well as his bestseller An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us.

KH: Throughout your book, I couldn’t help but notice that you’re very well informed about a multitude of scientific topics from chemistry all the way up until physics. For aspiring science writers, can you talk about your educational background and how you got to where you are today?

EY: I studied a variety of scientific disciplines. I did chemistry and physics in high school. When I was in university, I did a course that covered a wide range of different sciences, from biochemistry to organismal biology. I ended up with a mix of zoology and molecular biology. The latter is what I took to my PhD program. I spent two years trying to get a PhD before realizing that I was terrible at it and also temperamentally ill-suited to actual bench research.

I like learning about a wide range of different things rather than being laser-focused on one particular thing for many years. I like having very fast rewards for the work that I put in. I write a piece, I can publish it, and move on to the next thing. With research, it might fail [or] you might get a paper after two or three years. It’s too slow paced for me. I realized that I wanted to create much more than I wanted to actually do research myself.

So, I started writing about science in 2006, and I’ve never really looked back. I think I am intellectually voracious and like learning about a lot of different things. Most of those things are not areas that I studied in my education. I didn’t do microbiology, sensory biology, or any of these things, really. A lot of this is self-taught and self-researched, and I think that’s true for most of the really good science writers out there.

KH: I imagine you had a lot of edits before you actually reached your final draft or product. Can you talk about your writing process and how long it took to finish the book, as well as any slumps you had along the way?

EY: Once I have the idea, I spend the first half of the timeline (about a year or so) doing some really intensive research and organization. I’m very, very big into structure. I need to have a very clear sense of what the book is about, what the chapters are going to be, how they’re going to be ordered, who are the main characters in each one; the macro and meso-scale structure of the book has to be completely worked out before I actually start writing. So, I spent that year just reading a ton of papers, doing some interviews, [and] going on field trips. [I also thought] through what the book was about, what the major themes were for each of the senses, and then I started writing. I think I wrote for nine months to finish the book. The biggest snag was the arrival of a global pandemic in the middle of that. I put that work on pause for about eight months or so. This is the same pattern that I’ve had for the first book and that I’m now recapitulating for book three: just a huge amount of thought and preparation for the actual writing.

NL: As I was reading the book, I saw this clear structure: we start out with the chemical senses and then move on to the mechanical ones. How did you decide to organize the book in this way, and were there alternate ways that you considered?

EY: That’s a good question. From the start, it was clear to me that the book would be organized with each chapter being about a different sense. It just made sense to organize it that way. I don’t think I considered any other structure. That’s kind of a gift. Sometimes when you work on a big project, it isn’t clear what the major sections should be. Having that clarity at the start was enormously helpful. Then, it really was a case of which senses [should be in the book]. Some were very obvious. Clearly, there was going to be a chapter on smell, but was there going to be a chapter on taste separate to that? There was going to be a chapter on vision. Early on, I had separate chapters on seeing in the dark and seeing in color. Obviously, the color one stayed, and the dark one got folded into the main vision chapter. With a lot of the mechanical senses, it was a little bit unclear how to separate those into different chapters. Chapters on vibration, touch, hearing, and echolocation all kind of flow into each other, and sometimes the boundaries between those are quite porous.

That actually reflects, I think, conceptual porosity, or the way people working on these senses think about them. [For example], whether feeling water currents or air currents counts as hearing or touch is kind of an unanswered question. I got quite conflicting answers when I posed it to different people. So, thinking about how to organize those chapters was challenging and required a lot of thought. But, I think other than that, the ordering of the chapters in the book is more or less the order that I planned right from the start in the book proposal. [My team and I] were going to go to the more familiar senses first, and the stranger and more exotic ones (like sensing of electric and magnetic fields) would be right at the end, and it would end with a chapter on sensory pollution.

The biggest change that we made to the structure of the book was in the editing process. Originally, I had the vision chapters first, with the logic that for those of us who can see, which is most of us, vision is primary [and] dominant. It’s the sense that we rely on most and that most reflects our culture. Surely we should begin with that. It was my editor, Hillary, who very rightly suggested, ‘I think you should put smell first.’

There were a few good reasons for that. One was just that we wanted to hit people with something that they were sort of familiar with, but not too familiar with. You want that Goldilocks spot where it’s not too jarring an introduction, but it’s jarring enough to give people the sense of a very different world than what they’re used to. I think the very smart reason to put that first is [because] after the introduction, the first animal people encounter is the dog. If the vision chapter was first, then the first animal they would encounter would be the jumping spider. It’s just much, much easier to get people invested if you lead with dogs than if you lead with spiders. You want to earn people’s trust before you hit them with waves of spider content.

NL: That makes total sense. Speaking of jumping spiders, I saw that Elizabeth Jakob [who studies jumping spider perception] is in Amherst, Massachusetts.

EY: Yes, that’s right.

NL: So, your research for the book has taken you all over the world it seems, including to our college town. How did you decide what scientists to visit? Did you have trouble choosing between experts?

EY: I had a big database of all the people who were doing cool work whom I could potentially see. It had a couple hundred names, and it was organized by centers, animals, and locations. If I was doing a talk in North Carolina, then I could see who I could potentially talk to there and opportunistically arrange some lab visits. But, it really came down to thinking for each chapter. Where could I go that would give me the most interesting scenes? By that I mean characters, experiences, events, [and] settings that would make the themes of the book come alive. I’m paying for these trips out of my own pocket, so there are some limits to how many I can do. Each of these is going to be relevant to only maybe a 2,000 word section of the book, so I don’t want to do one for every one of those sections. That seems overkill. Where can I get the most bang for my buck?

With the vision chapter, I guess the most ludicrous example is I could have tried to go on a submersible trip to see a giant squid, but that was probably not going to be a sensible use of my time or money. The jumping spiders stood out because I knew about Elizabeth’s work [and] I knew that she had the spider tracker set up. I knew that I could probably go and see some kind of experiment in action and interact with these spiders that were very self-contained, [which was] much easier to find than, say, a giant squid. I got all of that. It really was a case of trying to map out who the protagonists were, and by that, I mean the animals and the people. Is it going to be good enough for me to call them on the phone and talk through their work? Or, will I get something above and beyond that if I’m actually there? How many of those visits can I tie together to make it as efficient for the reporting as possible?

NL: It seems so worthwhile tapping into the human side of things in all the anecdotes that you share in your stories. A question related to that: you use humor a lot to get ideas across. We have the example of the river full of electric fish being described as ‘a cocktail party where no one ever shuts up, even when their mouths are full’ (289).

EY: Right.

NL: I’m wondering, do you think that comedy is a useful way to communicate scientific ideas when used properly? Is it being underused right now?

EY: ‘When used properly’ is the crucial part of that question. I think if you try and do it badly, it’s worse than not doing it at all. If you go for it, it really has to land. I think the secret to making it work is to almost not try. It’s not like I’m writing that phrase about the electric fish thinking, ‘I need a gag here.’ I’m not writing a bit. That actually just happens to be, I think, the best description of what is happening, and it just so happens that it’s lighthearted and a little glib. Actually, that’s sort of where I tend to skew anyway. I am not overly serious, even when I’m writing about quite serious and complicated things and especially when I’m writing about the natural world. Animals have this incredible combination of being both awesome in the original sense of the word but also of being really absurd. Animals are goofy and silly, and they do ridiculous things. I think that good science and nature writing really embraces both of those sides. That’s sort of what I wanted to do with this book. If you understand that, then you don’t have to reach for comedy in a cringey way. Actually, nature is just kind of funny without you needing to try that hard.

NL: Alongside that last question, you’re dealing with some pretty philosophical questions at times. You ask about pain existing with and without consciousness (130) and you bring up Descartes (122) — were you prepared for that kind of overlap of philosophy and science?

EY: Yes. It was one of the things that drew me to this topic in the first place, and [it] actually runs through the things I’m most interested in. Some of the most interesting aspects of science make you rethink aspects of the world that you thought were familiar. In [that] process, you cannot just rely on the products of the scientific literature. Philosophy is crucial here, [just] like [in] Thomas Nagel’s What Is It Like to Be a Bat? [This was] very much an anchoring piece for [my] book and entire domain of work and thought. [This book] was both scientifically fascinating, but also philosophically rich, which is why I thought this [was] a topic worth exploring.

NL: I certainly agree. A lot of the times when you are crafting your prose, you’re doing it in a way where you’re being straight [and forthright] with the reader. You mentioned this one study titled “Cooler Snakes Respond More Strongly to Infrared Stimuli, but We Have No Idea Why” as a refreshing example of academic straight talk. Do you see forthrightness and the ‘telling it how it is’ [attitude] in short supply in academia? Is that where you see yourself fitting in as a science writer?

EY: Well, that’s a really good question. A little bit. I think academia has a degree of formalism that is not useful. You’re often writing with serious stuff, like very technical things. I get the necessity for having jargon-filled, strait-laced descriptions of the work. This is not a place where people should go nuts with comedy, and often when [people] try, it doesn’t work. Yet, that formalism translates to a view of science as being cold, clinical, and detached from the human experience. And I think that’s just nonsense.

Science is a very human endeavor, and it is interesting that the scientific literature doesn’t reflect that in almost any way. You get very little of the story behind how and why people do the work they do. You get very little of that philosophy that we talked about. Every scientist I talked to (almost all of them) has an answer to the question of, ‘How do you think the animal you study experiences the world?’ [This is] because they have thought about it, [and] it’s a very natural thing to think about, but it’s not in their papers, right?

A lot of these papers are obscured by technical language, by passive tense, [and by] all the cultural norms of scientific writing. [This is] not because those norms are useful in terms of communication, but because they present the code for seriousness that I think is actually not useful. So, do I think that my role as a science writer is pushing against that? A little bit. I certainly don’t think my job is to translate the scientific literature, but all of those things I talked about are part of what I’m trying to get at with this work: I’m trying to show science as a human endeavor and get at the stuff that’s missing from just a pile of [research] papers. I mean to get at the background, motivations, [and] philosophical thoughts that go into them.

Parts of [my] book are not just about what we know about the animal world, but the construction of that knowledge (how we came to know those things). I think that is equally important to me. So yeah, I think that’s a really, really good question. And it does get at some of the things I’m thinking about as I’m producing this work.

NL: I have one last question about your role as a science writer before Kyle closes us out. Obviously, science is changing all the time. For all we know about magnetoreception, for example, we still don’t have a sensor for it. So when science changes, is it the job of the science writer to go back, update their past work, [and make it] the most up to date?

EY: I think that’s a really smart question, too. I don’t think it is an obligation. And certainly, if it was, it would be an impossible one. I have written, since 2006, [maybe] 5,000 pieces. I’m just thinking about what it would take to, on a rolling basis, revisit them all. It just wouldn’t be possible.

Sometimes I write about things that get refuted, papers that get retracted, or stories that get more complicated. [In those cases], I do revisit, especially if they are big [and] impactful. If a story goes viral and the paper is called into question the next week, I feel some responsibility to say, ‘No, this thing I wrote is more complicated.’ But I also think that these pieces, by necessity, are like a snapshot in time. No one is telling researchers who published things in the 60s that they need to go back and update their work. It’s understood that a paper in the 60s reflects the knowledge that we had at the time, and so it is with science books, too.

That said, I do try and make [my] work as timeless as possible. With An Immense World, some details might change, like we might discover which of those three magnetoreception hypotheses that I wrote about is correct. And maybe it’s not any of the three, or maybe it’s all of them. There may be other things I wrote about in the book that turn out to be very wrong.

In the main, I think that I have planned and written it so that those things will be fairly minor. If changes occur, like in the magnetoreception case, readers are forewarned about it. I said this is an area of controversy that might change. I don’t think the big ideas will change; it’s not like we’re going to wake up tomorrow morning and learn that all animals see the world the same way. I write about big ideas, like how vision works or what smell is for, because they have a huge amount of research and thought behind them. The hope for all the books, pandemic work, and bigger things I do is [that] the details might change, but the bigger picture, as presented, is going to be pretty solid for the rest of my lifetime.

KH: I just wanted to ask one last general question. Do you have any words, advice, or anything you’d like to share for upcoming science writers?

EY: Yeah! On my website edyong.me, I actually have a page with a bunch of advice for young science writers. So first look at that. But then, the things I usually say are [to] read widely and voraciously. Most of the techniques and tricks that I used in my writing are actually fairly obvious on the page and easy to reverse-engineer. You can look at how a writer uses structure, how they start a piece, and how they end a piece. Those things are actually fairly obvious, but invisible. You can see them being used and ask questions about how they’re used. There’s a lot of active learning that you can do [by] just reading work that you intuitively feel is good.

And then, just do the work. I’ve often said that writing is intentionality times practice. It’s being very clear about what you’re trying to do at every scale of writing: knowing what a chapter is about, what a section is about, what a sentence is for, and what word choices you’ve made. The thing I said about reverse-engineering pieces sort of gets you to a place where you actually understand what you’re trying to do with what you’re writing. [If] you do that enough times that it becomes second nature, [writing] becomes quicker and a bit easier. And that’s where the practice comes in. One of the keys to good writing is just to write and not trip yourself up by seeking perfection in every way. I think [it’s important to] understand that you need to produce things in order to get better at producing them.

And [lastly], look after yourselves. Writing is a tough industry (journalism in particular is just brutal right now). It can sort of grind you up and spit you out, but the natural world is wonderful. There is a lot of need for good writing about science, health, and nature. It’s an incredibly rewarding thing to do, so I hope you all have the best of luck with it. I hope you stay sane and motivated.

Check out Ed Yong’s talk at LitFest on Sunday, February 25 at 3pm in Johnson Chapel.