On April 14, the Amherst College Department of History hosted the 2020-21 Hawkins Lecture, “Why Diversity Makes Science Not Just Fairer, but Better,” with Dr. Naomi Oreskes. The Henry Charles Lea Professor of the History of Science at Harvard University and author of Why Trust Science? walked us through a fast-paced and compelling presentation on the history and necessity of diversity. It is often the moral and ethical aspects of diversity that are focused on, but there is also an epistemological (or knowledge-based) argument. Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) have become cultural touchstones recently, and for good reason.

Since the 1960s, America has grappled with problems of overt discrimination. The three examples that Orestes gave concerned women’s gains in the medical, legal, and political fields. Medical colleges in the US were in a state of “apartheid” in the 19th century, with separate colleges for women. This discrimination was due in part to the limited energy theory promoted by Edward H. Clarke, M.D., that if women took on the rigors of higher education, their uteruses would shrink. This asymmetrical approach did not consider any effect on men or, Orestes cheekily commented, “which part of their anatomy would shrink.” However, women now represent 50% of medical students. Similarly, in the field of law, most women were excluded from top law schools in the 1960s. Those who did manage to attend, such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg, were marginalized. Now, women are about 50% of law school students. In the realm of politics, representation of women didn’t start to seriously develop until the 1990s, but at this moment the US has the most diverse Congress in its history.

Although women in these three fields gained ground towards equality, Orestes noted that “there is still a lot of resistance to purposefully expanding diversity, particularly in science.” The main arguments that exist now for DEI are fairness and talent, and “few people openly disagree with either of these arguments.” However, the main argument against DEI is what science commonly calls “our commitment to excellence.” Many scientists truly believe that science is a meritocracy, so they see no need to disrupt existing power structures. Furthermore, “many scientists believe that the goal of DEI is in conflict with the goal of excellence.” There is a perceived tension between inclusivity and maintaining the highest intellectual standards. Orestes argues that this framing has the problem backwards.

First, we need to back up and answer some fundamental questions. One, what is the goal of science: to find out truths about the natural world. Second, how do scientists do that: Orestes stresses that there is no one scientific method that yields the truth. Third, then how do scientists find truths about the world: they collect evidence. With all of these questions answered, Orestes moves our attention to how this process is directly impacted by diversity. After the evidence has been gathered, it must be vetted. “Scientific claims are subject to tough, critical scrutiny,” and there are boards designed for the sole purpose of reviewing findings before they are released. Through discussion and criticism from colleagues, scientific claims are modified and improved. Philosopher Helen Longino refers to this process as “transformative interrogation.” Orestes tells us, “scientific ‘facts’ are claims that have withstood this scrutiny.”

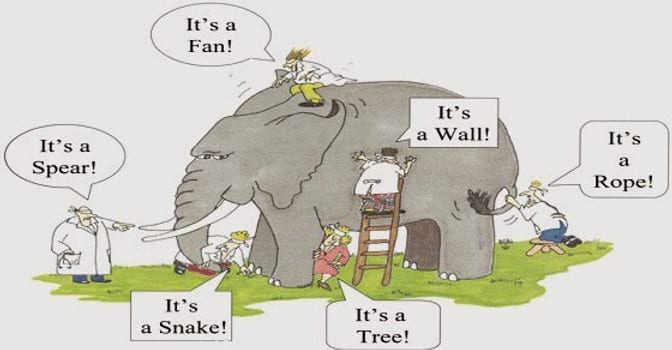

This leads us to an idea that we have always been told, and usually believed: science is objective. Furthermore, the reason “that science works [is] because it is objective.” Orestes disagrees. She says that “objectivity is a ‘regulative ideal.’” People place high value on this trait, because they believe that if science is not objective, then it will be slanted or have questionable motivations. However, the opposite of objectivity is not bias, but subjectivity. Orestes stresses that subjectivity is not bad; it is unavoidable. People look at the same objective reality and all have different subjective interpretations of it. Everyone sees things in different ways.

The clincher in Orestes’ argument, therefore, is that “a scientific community that is homogenous will tend to look at things in the same way.” Every scientist brings their own values, preferences, and biases to their work. This is not something to be demonized, but to be taken into account to make positive change. Having scientists of diverse backgrounds ensures a wide range of perspectives, all of which are valid and valuable. This also helps to create a version of science that is universal, not the result of one group.

Orestes concluded with the point that “a diverse community is not ‘politically correct.’ It is more likely to generate scientific claims that are actually correct.” It is imperative to make sure that under-represented people aren’t just in the room, but they are heard. Science alone is not enough to fix the problems of the world. We need a reliable interface between science, the public, and politics. We need to be able to communicate, both among ourselves and to others.

You must be logged in to post a comment.