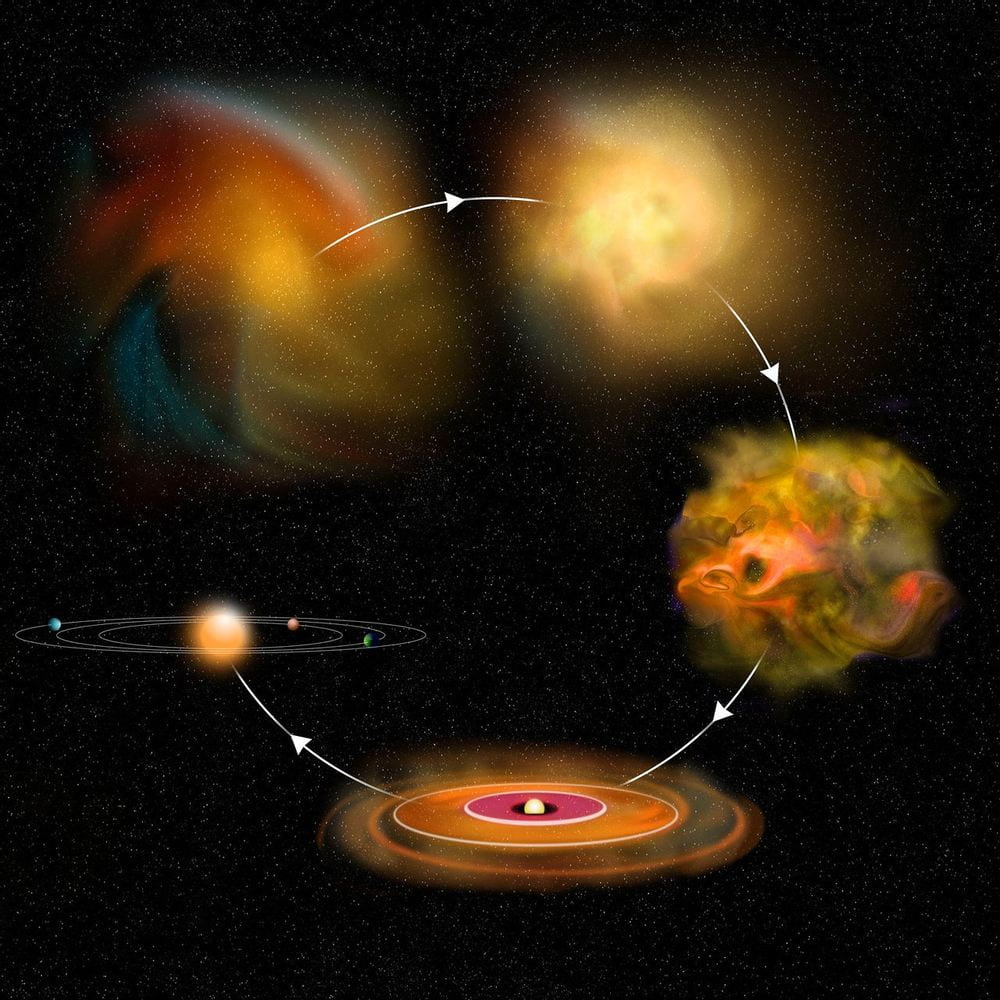

Solar systems like ours begin as pancakes of dust and gas left over after a star forms. Over time, the dust within these “circumstellar disks” coagulate into planetesimals that will eventually form planets like the Earth. During this early stage of solar system evolution, these circumstellar disks are called “protoplanetary disks” because planets have not fully formed within them. Feng Long, the Submillimeter Array (SMA) Postdoctoral Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), spoke at the Five College Astronomy Department (FCAD) Fall 2020 Virtual Colloquium hosted by UMass Amherst on Thursday, October 29. She discussed her recent publications and the implications that these incredibly detailed observations have for our understanding of solar system formation.

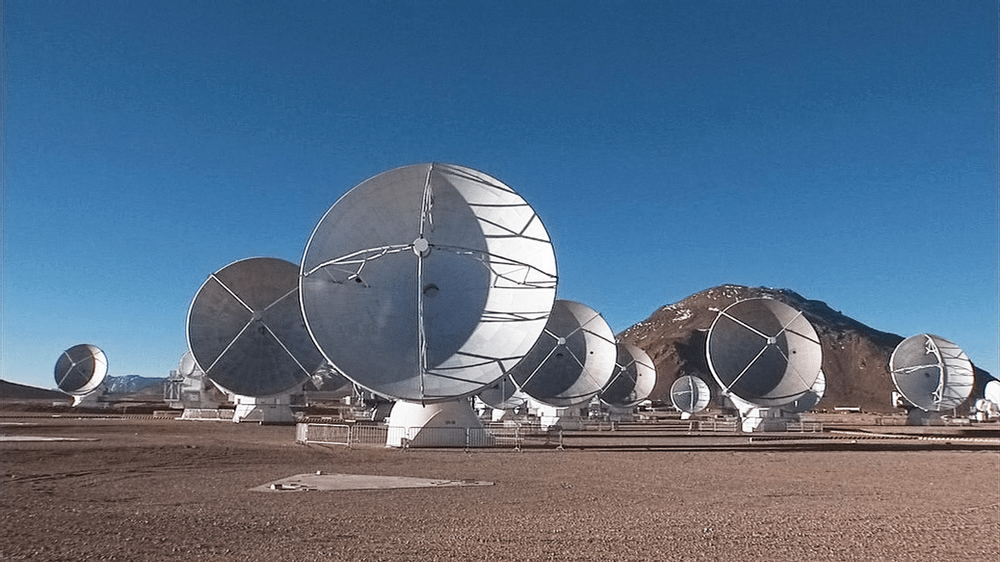

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has operated since 2013, taking observations of the sky in long wavelengths of light. Circumstellar disks are cool, so the light they emit is of a much longer wavelength than hotter targets like stars or planets. ALMA has many antennas working together to build baseline lengths extending kilometers, enabling astronomers to take high-resolution images of the dust and gas that encircle young stars.

As Long explains, the mass of the dust within a protoplanetary disk informs a number of relationships. The dust mass is related to the mass of the host star by a scale factor. Put plainly, a heavier star has a heavier disk around it. She determined this by studying the nearby Chamaeleon I star-forming region (,,2018a). She found that there is not enough mass within the disks she surveyed to create most observed planetary systems. The lack of mass does not mean these disks cannot form planets. Instead, the planets have probably already formed within these disks, meaning planet formation likely happens much earlier than astronomers expected and indicating that planets likely generated many of the features Long observes. She presents ALMA observations and her models of these rings and gaps here (,,2018b).

There are many problems with the current theories of planet formation, and an important one is the “radial drift barrier.” This problem arises because dust grains must grow by more than ten orders of magnitude in size (from tiny grains like sand, to giant boulders) in order to form planets. This process takes a long time, but physics tells us these dust grains quickly fall towards the central star as they gain more mass. According to current physics, planets should not be able to form because the planet-forming material will have fallen onto the star before growing to the size of a planet. Long says that pressure bumps in the disk’s gas might trap dust particles in rings and vortices. Pressure bumps are generated within a disk by a variety of physical processes (solidifying ices, other planets, and hydrodynamic instabilities), and would act to keep dust from falling inward, allowing the growth of planetesimals.

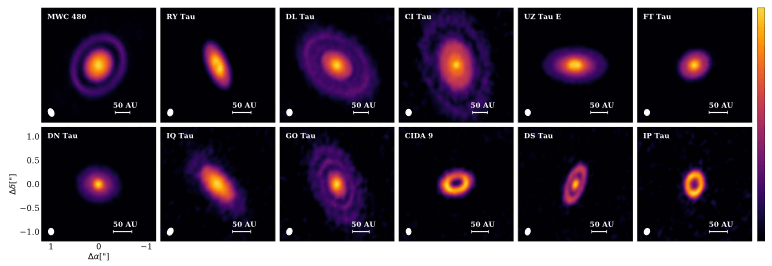

While other ALMA observations have published images of bright disks with lots of rings, Long explains that this preference towards bright disks (and therefore better-looking results) is not population sensitive. She presented a survey of disks in the Taurus star-forming region (,,2019). This survey sample had no population bias, so she was able to make definitive statements about the protoplanetary disk population in Taurus. She showed that: 1) substructures are visible in both bright and faint disks, 2) axisymmetric rings are the most common type of feature in the disks and that there is rarely azimuthal asymmetry in the disks, 3) spiral arms are rare features that only occur in bright disks, 4) while rings are common, the weight and size of the rings vary widely, and 5) while some rings correspond to the locations of frozen ices, others do not. This indicates that planets or hydrodynamic instabilities carve some of these rings.

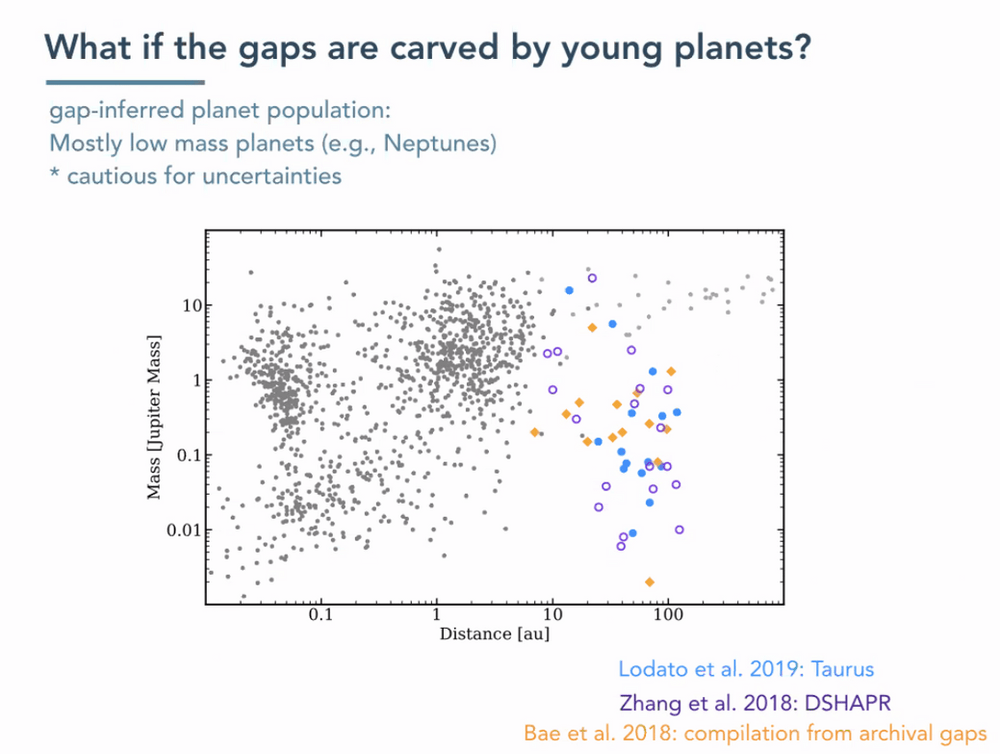

She then showed that modeled planets which could replicate these rings would fill in a missing puzzle piece in our understanding of exoplanets. These hypothesized planets are mostly low mass Neptunes and are widely separated from their host stars outside 10 AU. The exoplanet detection methods astronomers use are biased towards close and massive planets, but these hypothesized planets are far away and low mass. In the figure below, the gray points represent exoplanets found by astronomers to date, and the colorful points represent the hypothesized gap carving planets.

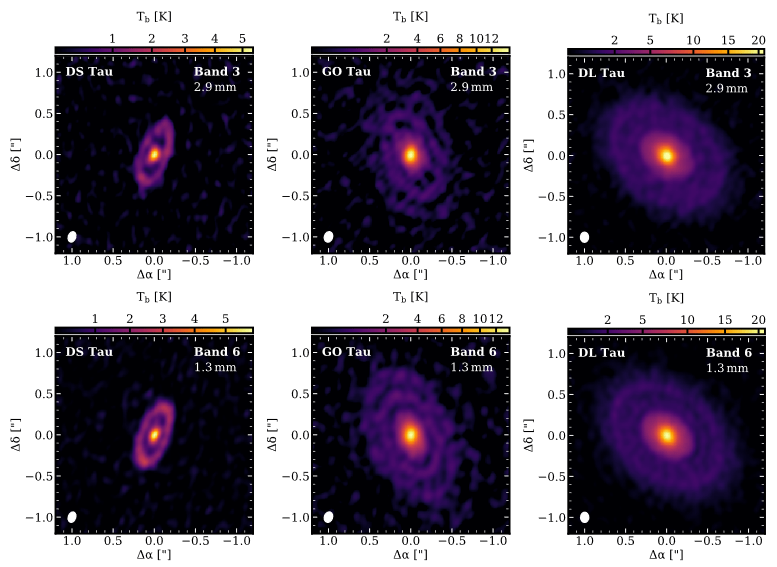

Long then discussed her most recent publication in which she observed three disks at different wavelengths and compared her observations across wavelengths to determine the origin of the observed disk features (,,2020). While inner disks are smaller at longer wavelengths (which is predicted by radial drift) dust rings exist at the same distance across wavelengths, meaning that dust particles of different sizes are all trapped in the same ring by some mechanism, such as a pressure bump generated by a planet.

Long’s research uses a state-of-the-art telescope to unravel mysteries surrounding the origin of solar systems like our own. Her results will tell us how unique our solar system really is and how we got here. Her presentation is just one of the many fascinating colloquia held by the Five College Astronomy Department. To keep up with astronomy news from Amherst College, subscribe to the Amherst STEM Network mailing list, and follow our ,,Instagram!