Host: Aditi Nayak ’23

In today’s podcast, we introduce you to Professor Rachel Bernard. She started as a Visiting Geology Professor at Amherst the Fall of 2019 and studies rocks that come up from the lower crust and upper mantle portions of the earth through volcanic eruptions. Today, we talk about her journey from being a prospective Engineering student at Princeton to becoming an Amherst Professor. We also talk about what her research entails and her thoughts on diversity in the field. A transcript of this podcast is available below.

Timestamps:

[0:00] Introduction

[1:48] Who is Professor Bernard?

Background

[2:55] Where did your interest in geology start? Was it something when you were younger and people asked you what you wanted to be when you grew up, did you always respond to geologist or is it something you grew into?

[4:59] At Princeton, what was the first geology class you took and what was your first impression?

[6:37] How did you find your way back to grad school and academic geology?

[8:58] Even though you decided not to stay in those positions, how did these early careers shape your eventual decision to become a geologist?

Research

[10:54] All these questions are leading to what you do now, so what do you research?

[13:56] When you finally acquire these raw materials what are you looking for in them?

[16:07] What’s the story that your research tells? What are the implications of your research?

Encouraging Participation in Geology

[18:50] How do you get current students interested in geology? How do you encourage others to pursue geology?

[21:56] What specific actions do you take to point out diversity issues in geology and to fix the lack of it?

[24:25] What are some misconceptions about geologists?

[26:00] What advice do you have for prospective Geology Students?

Conclusion

[27:11] Where can students find you the rest of the semester?

[28:58] Do you have any last pieces of advice for our audience?

[30:29] Conclusion

Credits:

Publisher: Amherst STEM Network

Podcasts Coordinator: Julia Zabinska

Music Composer: Grace Geeganage

Cover Art Designer: Chloe Kim

Cover Image Credit: https://www.rachel-bernard.com

Transcript:

In today’s podcast, we introduce you to Professor Rachel Bernard. She started as a Visiting Geology Professor at Amherst the Fall of 2019 and studies rocks that come up from the lower crust and upper mantle portions of the earth through volcanic eruptions. Today, we talk about her journey from being a prospective Engineering student at Princeton to becoming an Amherst Professor. We also talk about what her research entails and her thoughts on diversity in the field. Below is a transcript of this interview so that you can follow along. If you would like to learn more about Professor Bernard, you can visit her website here.

[0:00] Hello, and welcome to one of the first episodes of the Amherst STEM Network’s podcast! My name is Aditi Nayak, your host for today’s episode. While we’re recording this may not have an official name yet but it does have this super catchy theme song:

[0:36] If you haven’t listened to episode 0 yet, where we introduce the podcast, one of the things we want to do is make STEM less intimidating by talking to the people in STEM at Amherst. At the end of the day, all of us (professors, students, and faculty), we are all doing our best to understand the world around us. That’s the core message of our podcast.

In today’s podcast, we introduce you to Professor Rachel Bernard. She started as a Visitng Geology Professor at Amherst the Fall of 2019. And now, she studies rocks that come up from the lower crust and upper mantle portions of the earth through volcanic eruptions. Today, we talk about her journey from a being prospective Engineering student at Princeton to being an Amherst Professor. We also talk about what her research entails in specific and her thoughts about diversity in the field. A transcript of this interview is available at www.amherststemnetwork.com, where you can follow along with the audio and see images of the samples she examines. Okay, without further ado, here’s our conversation with Professor Bernard.

[1:48] Hello Professor Bernard! Thank you so much for joining me today. You are a relatively new Geology Professor at Amherst. You’d mentioned this upcoming semester will be your second year teaching at the college. So, for anyone listening who has not yet had the pleasure to meet, who are you?

Sure. So I am about to start my second year at Amherst college. I’m a visiting assistant professor in the geology department. I teach structural geology, and I will also teach intro geology eventually. But for right now I’ve been teaching structural geology, which is an upper level course for majors. It focuses on the part of geology that I am really interested in which is how rocks deform and how they break and kind of the physics behind all of that. And how tectonic plate movement affects rock deformation.

[2:55] Where did your interest in geology start? Was it something when you were younger and people asked you what you wanted to be when you grew up, did you always respond to geologist or is it something you grew into?

So almost every geologist that I’ve met that’s a professional geologist didn’t know that they liked geology, and they ended up falling in love with it in college where they just happened to take an intro course. Or, maybe they didn’t even want to do STEM but they had to do some science class and they did geology and they really liked it. So for me, it was a little bit similar. I went to undergrad at Princeton, and I enrolled as an engineer and I didn’t really know what that meant. I just knew that if in high school, if you like science and math, people tell you that maybe you’ll like engineering. So I did engineering and I was in environmental engineering, that was my declared major. But they didn’t actually do the intro to environmental engineering until sophomore year. So I was so excited and then I finally started intro to environmental engineering and I hated it. So boring! And it was like all chemistry. And I didn’t really realize how much of environmental engineering was chemistry and volatiles in the atmosphere. I kind of panicked and I didn’t know what to do, and luckily I had a part time job helping a senior with this thesis research. So all I had to do was hold an instrument for him and he did kind of stream work. I told him about my problem and he said, “Oh, you should major in geological engineering. That’s what I do. And it’s really fun.” I was basically so desperate that I just signed up for it. Because I was running out of time and it was pretty much the only thing I didn’t need to take more prerequisites for. So I signed up for it and took my first geology class junior year, and I loved it.

[4:59] At Princeton, what was the first geology class you took and what was your first impression?

Yeah, because I didn’t find geology until my junior year, I kind of had to jam pack a lot of classes at once, so I took intro at the same time that I took some atmosphere and oceans class. It was great. I liked it immediately. ntro geology was the first time that I actually wanted to ask a question in class. In the past, I had just done it because I wanted to participate and get my points, but I didn’t actually really care what the answer was. But in intro geology, I was like “Tectonic plates! I actually want to find out more about this.” So I was actually asking questions and I still ended up majoring in engineering cause I did geologic engineering. It actually took me several years after undergrad to even realize that geology was something I wanted to go to grad school for. I was so burnt out and tired after undergrad, and I didn’t really like my senior thesis experience or how it went. I was kinda done with school. I was just like, “I have an engineering degree. I don’t need to go to grad school.” It wasn’t until kind of years later that I really thought back “Oh, actually I did like geology classes. That was cool. Maybe I should go to grad school for it.”

[6:37] After graduating from Princeton wanting to not continue in education, it’s interesting that you are now a Visiting Geology Professor at Amherst. How did you find your way back to grad school and academic geology?

Yeah. Because I had an engineering degree and no interest in continuing education at all, I went and worked for an oil field services company. So it’s a company called Schlumberger and they hire field engineers to operate equipment for drilling oil. I worked on oil and gas rigs for two years after undergrad as an engineer. It was in the Gulf of Mexico, so offshore and some onshore in Arkansas and Texas. And I did that for two years and then it was not for me. It was definitely an adventure, but it was a very high stress, high adrenaline environment. “Oh, something breaks. We have to fix it in the middle of the night or else everyone’s going to be mad.” That was not for me. Luckily, I got a job after, after I’d been there for two years, I got a job working for the government. So I worked for the National Science Foundation, uh, in Washington D C, which I was really happy about because my parents live there. I worked there for two years, and that was really where I started to go back to geology and think about grad school because I worked in the Division of Earth Sciences. And basically what NSF does is they fund a lot of the scientific research that people in academia are doing. So I’m working in the division of our sciences and reading all these proposals that are coming in, if people that want to do all these cool science projects and everyone I’m working with basically has a PhD in geology. And they’re really nice. Basically while I was working there is when I decided that I could go back to school and do it. And grad school’s a lot different than undergrad. So then I applied to grad school, did a PhD and did a postdoc, and now I’m here.

[8:58] Even though you decided not to stay in those positions, how did these early careers shape your eventual decision to become a geologist?

The thing that really made the biggest difference for me, and one thing I really struggled with is it took me a long time to figure out what I’m going to focus on in grad school. Because in the sciences and most scientific disciplines, when you go to grad school, you’re applying to work with a specific person on a specific project. It’s not just like I’m going to apply to UT Austin and do a project with I don’t know who. You have to find a person and whatever school they happen to be at, that’s the school that you go to. When you contact them, you have to have kind of some sense of what you’re interested in, which is really hard. So when I was at NSF, I was able to go to a big scientific conference. It’s the American Geophysical Union annual conference. It’s tens of thousands of people, really big, a lot of people from space science and atmospheric sciences and geology, go there. I kind of was overwhelmed and didn’t really know what I liked. I knew I kinda like physics and rock deformation but that was pretty much it. I was really lucky that I met a postdoc at her posters. She had a poster there and it was a really pretty poster and the rocks were really cool on the poster. I got to talking to her in any way. She ended up being an assistant professor at UT Austin, and so when she got that job, I applied to work with her. That’s how I got into my specific area of research.

[10:54] All these questions are leading to what you do now, so what do you research?

Yeah, so most of what I study is ductile deformation. So in the earth, rocks break. Near the surface where things are cooler and the pressure is lower, they break britaly, so you get things like faults and earthquakes. But when you go deeper towards the lower crust and into the mantle (which is the layer below the crust) things are still deforming, but they’re deforming ductilly. More like a silly putty: still a solid but stretching out, smearing over really long periods of time. So it’s very solid, but over a million years, it’s more of a flowing process. I study rocks that come from the lower cross and the upper mantle. I cut slides of the rocks and primarily looked at them under the microscope. Sometimes like a regular Microscope, sometimes an electron microscope, in order to look at the micro structures. I’m looking at the small atomic breaks that happen that allows this silly putty-like flow behavior.

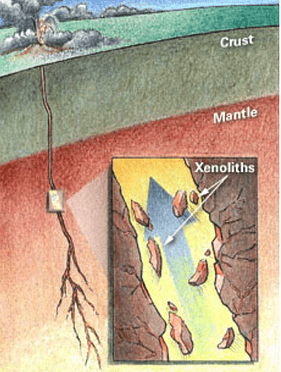

Image 1: How mantle xenoliths are brought to the surface by volcanic eruptions

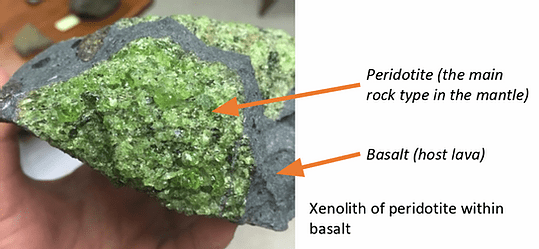

Image 2: An inactive cinder cone volcano that brought xenoliths to the surface a couple million years ago. Location: Mojave Desert

The main rocks that I use for this are called xenoliths, and they’re really cool. Backing up, we can’t drill into the mantle. Theoretically, we probably could, but we haven’t yet as a species or society cause it’s really deep, really hot all equipment breaks. So one of the few ways that we’re able to get rocks from the mantle is these volcanic eruptions. There are specific places around the world, different localities, where volcanoes have actually erupted from so deep that they’ve been able to grab chunks of rock. So the magma erupts and grabs chunks of rocks on its way out and spits them out at the top. Those are called xenoliths because it’s a Greek word from the same root word as xenophobia: it literally means stranger rock. So it’s like a rock, a weird rock that’s within another rock. I go to old volcanoes and walk around and look for pieces of the mantle or the lower crust and study them.

[13:56] When you finally acquire these raw materials what are you looking for in them?

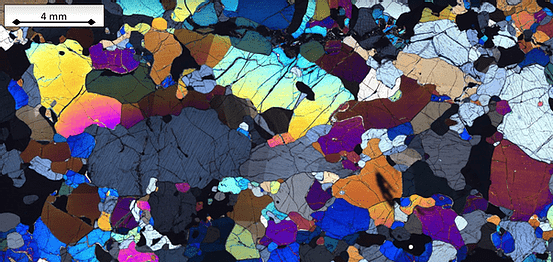

So mineral composition is important. Mineral composition can really help you figure out how deep the rock came from. Under the microscope, we can see some really strong evidence for deformation. When you have just a normal rock where crystals form and they cool, but nothing deformation related happens, the crystals are kind of nice and happy and maybe they’re like nice equate sizes: they’re not too long in one direction or too short. They’re just kind of, you know, a shape of a crystal that you’d expect. Like when you go to a museum and see crystals. But in these rocks that have been deformed, the minerals can get really, really stretched out. So that’s one way that they show they’ve been deformed. So we can get crystals that should be shaped like this that are really, really long and smeared out. Then we also see in geology, we use Petrographic microscopes so they have these filters that allow you to see changes in the mineral structure that you wouldn’t normally be able to see because the deformation changes the optic properties and it’s a whole complicated thing, but you can see it and I can share some pictures. I can share some pictures with the, if you wanted just about, um, if you wanted to show people what, um, the rocks look like under our Petrographic microscopes, it’s really beautiful. They’re really crazy colors because we use polarized filters when we’re looking at our rocks. So it makes them all kind of crazy colors: pinks and purples and blues. It’s very beautiful.

Image 4: This is what a rock looks like under a Petrographic (geologic) microscope. The most abundant mineral in the mantle, olivine, is green in reality but appears bright yellow, pink, blue, purple, and green under the cross-polarized filters we use in these types of microscopes. The gray colored crystals are the mineral orthopyroxene (second most abundant mineral in the mantle). The filters help us visualize many geographic properties in addition to aiding in mineral identification.

[16:07] You can tell a story through rocks. What’s the story that your research tells? What are the implications of your research?

Well, one thing that I find really interesting is how deep do defaults go. The traditional thought behind faults is that they only exist where rocks deform britally, so in the upper part of the crust and then they just stop. So you have this fault and then it stops. But what we know more recently is that really big faults, like the St. Andres, for example: there’s some discontinuity at the top that’s brittle. That’s where the plates are rubbing past each other like that. And then when you get down lower, there’s still a concentration of deformation. Like you have this zone, which we call a shear zone, where rocks are really, really highly deformed and they’re smearing and deforming a really concentrated region. As you get farther and farther away, they become less and less and less deformed. That’s not how faults work cause we have deformation and then no deformation, cause it’s just a very discrete discontinuous contact. But we know from geophysical surveys that the San Andreas and seismic profiles that San Andreas actually goes all the way to the MOHO. So the MOHO is what we call the boundary between the crust and the mantle. And we can actually see that beneath the San Andreas, the MOHO has a little break in it, which tells us that the fault is going super deep, all the way into the mantle. And that could have real implications for how people model earthquakes. If you’re modeling an earthquake and you have to put in your parameters, one of the things is depth. You’re not going to be able to model exactly how far your earthquakes propagate or how often that might slip. If you’re doing any sort of modeling with earthquakes, you’re going to need to know how deep the fault goes and what’s going on beneath the fault. So a lot of what I do is look for evidence of rocks being deformed in that way, in the mantle from shear zones.

[18:50] Backtracking a bit now, earlier in our conversation you mentioned that you went into undergrad for engineering because people said if you’re interested in math and science you might like engineering. Quite honestly, that happened to me too last year when I was applying to colleges. How do you get current students interested in geology? How do you encourage others to pursue geology?

So, I really enjoy doing outreach. I think a hard thing about geology is that it’s one of the few sciences that people just don’t take in K through 12. When I was in my junior year of college and being blown away by all this intro geology stuff, it’s because I had never learned anything about it. And that’s probably why it was so exciting for me. It never had an earth science class, never had anything. And so it had never even occurred to me to think about a rock. Like I never would’ve even thought about it.

I want to see geology become a much more diverse field. It’s the least diverse STEM field actually in this country. And I want to see more diversity. I think one of those is introducing all different kinds of people to geology, to even put it on their radar and say this is cool. You can have a lot of different, awesome jobs with geology and here’s what geology is. I’d like to get more people at Amherst to take geology, especially next spring when I’m going to be co-teaching intro 111. That’s a big thing. Just increasing diversity in geology is a really big passion of mine. One of the things that I’ve been spending a lot of time doing actually is just trying to convince people that it’s a problem that geology isn’t more diverse.

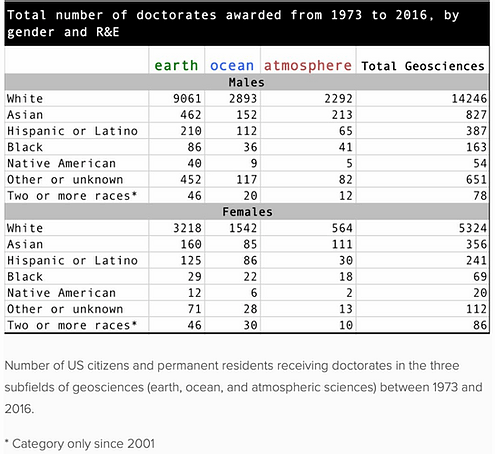

Image 5: The data above is from a study conducted by Professor Bernard to assess diversity in geology. The full paper can be found here.

How I’ve done that is by collecting data on who is actually studying geology and in particular who’s getting PhDs in geology and what their demographics have been. I think by showing a lot of other geologists that these numbers are really small. It’s not just that you don’t know people or maybe it’s not just that your department doesn’t have a lot of people. Our whole field is very white. Even just pointing that out I think is a good step. What we do about that is very, a lot more complicated.

[21:56] I’m so glad you brought that up because I feel like this summer in particular has showcased the lack of diversity in STEM. What specific actions do you take to point out diversity issues in geology and to fix the lack of it?

Well, actually our department has been talking a lot. All summer, the faculty and a lot of the students have been having these conversations about diversity in geosciences, particularly at Amherst, but we’ve been doing some readings about why geology has this problem in particular. An example of one thing is the messaging we put out about geology. Most people that are currently geologists or traditionally are geologists do it because they love camping. They love being outside. They want to climb a rock or a mountain. They lived in a place where you see mountains. That is like a very specific subset of the population doesn’t necessarily apply to someone who’s from New York city, for example, and may not have been camping, may not want to go camping ever. I think we’ve done kind of a bad job as a group, not me, other people being like: “You know why everyone should major in geology? It’s because it’s cool and we go camping and it’s awesome.” I think that’s great. I love camping. I love being outside, but that can’t be our main selling point to people about geology because the fact is in modern times, like now, most geologists don’t do that. I work in a lab. I work on microscopes. Most of the people in our department do lab work. So that’s kind of more where the field is going anyway, so we just need to do a better job of showing people like geology is great. You can learn all these amazing things about the earth in a lab, on an oil rig, in a tent if you want. There’s a lot of different things like computer modeling. There’s a ton of different, diverse things you can do as a geologist. And I think we haven’t really done a good job of advertising that.

[24:25] What are some misconceptions about geologists?

Probably that everyone is outdoorsy and we all study rocks. There’s a ton of geologists who probably couldn’t identify one rock over another. I mean, I think that’s awful cause I love rocks, but you know, people that study fossils and people that study climate change. I think environmental studies is a great program at Amherst and really popular, and I think a lot of the people that are drawn to environmental studies would actually really like geology as well. I hope that they would take more geology classes because we use the rock record to look at past climates. If you’re doing things like going out on a ship and drilling down to the earth and looking at oxygen levels over time, CO2, that’s geology. You’re using the rock record to study something that’s important: climate change, evolution. I think that’s probably a misconception that we’re only studying rocks. It’s really that we’re using rocks and using what we can find in the earth to answer questions about everything around us.

[26:00] So for people who might be interested in taking geology or maybe are environmental studies majors that are on the fence, want to explore something new or people who just don’t really know too much about what geology is, what advice do you have for them?

My advice would just be to take intro, take 111.You learn a little bit of everything: you learn a little bit of tectonics, you learn a little bit of minerals and reading maps, get to go on field trips in a normal year–maybe not this year, I would just take intro. If you don’t like it, then maybe it’s not for you. But I think most people like intro geology and a lot of people take it toward the end of their time at Amherst and regret not taking it sooner.

[27:11]I’m guessing the best time to take geology would be when you’re teaching it in the spring 2021. So to any of our listeners, keep that in mind. Where can students find you the rest of the semester?

I have a new baby, so I’m trying to be extra cautious. And so I’m going to be working remotely from home. I’ll be super available remotely. After COVID settles down, I can be found in my office in Beneski, on the third floor. That’s where most of us geology professors have offices. I love my office. Got a nice window. It’s got a couch. You can come hang out, ask questions about rocks or not. That’s where I will be.

Oh you’re so lucky! Beneski is such a pretty building.

Yeah, well I really like all the minerals. There’s beautiful mineral displays all over Beneski that I highly recommend. Maybe people at Amherst don’t realize it, but this is the nicest geology building I’ve ever been in. When I came to interview here, I thought I was in a dream. I was like, are you kidding? Why are there so many beautiful rocks everywhere? Why is there a museum in the building? Like why is it this beautiful? So I think people should take advantage and I know that the museum is going to be open for people to be able to study this semester. It’s just a really beautiful space and it feels really nice. Just look at some nice looking, nice looking rocks and minerals and meteorites and fossils.

[28:58] As we wrap up this interview. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. Do you have any last pieces of advice for our audience?

My piece of advice is to really take advantage of all of the cool classes you have the opportunity to take at Amherst. Obviously be practical, but don’t just take classes cause you think it’ll look good or you really need that last technical class for your specific major. I mean, if you’re planning on going to grad school, your grad advisor is not going to be letting you take classes on Emily Dickinson, just for the hell of it. If you’re getting a PhD in geology. Now is the time to take classes and whatever is cool and interesting because when you go to grad school, you have to stick to your topic, which should also be quite an interesting but you know.

Take things that are fun. Don’t just do things that are practical. So that was what my problem when I was an undergrad is I thought I needed to do engineering because I want a job and that is the practical choice, but then I got that job and I hated it. And then where was I? Try your best to find something you really like to do. I know it can be really hard to be a long time to do.

[30:29] Thank you so much, professor Bernard for sharing your story and research with our audience. If you take nothing else from this podcast, please do take intro to geology because you may just end up thinking that geology rocks. Thank you so much for listening to one of our first tries at a podcast. Remember to stay curious, stay informed and stay tuned for more.